OWU Magazine Contact Information

Location

Ohio Wesleyan University

61 S. Sandusky St.

Delaware, OH 43015

E magazine@owu.edu

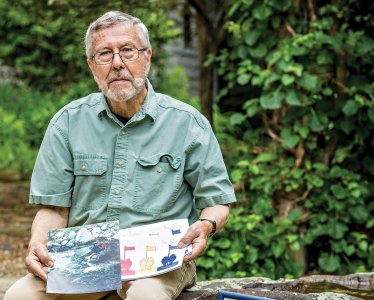

A father honors his daughter’s legacy by publishing the book she created while at Ohio Wesleyan

By Laura Arenschield

Molly LaRue ’87 was an adventurer who believed forests had the power to heal, and a creative soul who knew that art could bring people together. So when she and her boyfriend were found dead along the Appalachian Trail in 1990, after a brutal attack by a man who had been on the run after killing others, her family promised they would live as she would have wanted them to live — in concert with nature, making the world better for others, as artistically as they could.

Molly LaRue ’87 was an adventurer who believed forests had the power to heal, and a creative soul who knew that art could bring people together. So when she and her boyfriend were found dead along the Appalachian Trail in 1990, after a brutal attack by a man who had been on the run after killing others, her family promised they would live as she would have wanted them to live — in concert with nature, making the world better for others, as artistically as they could.

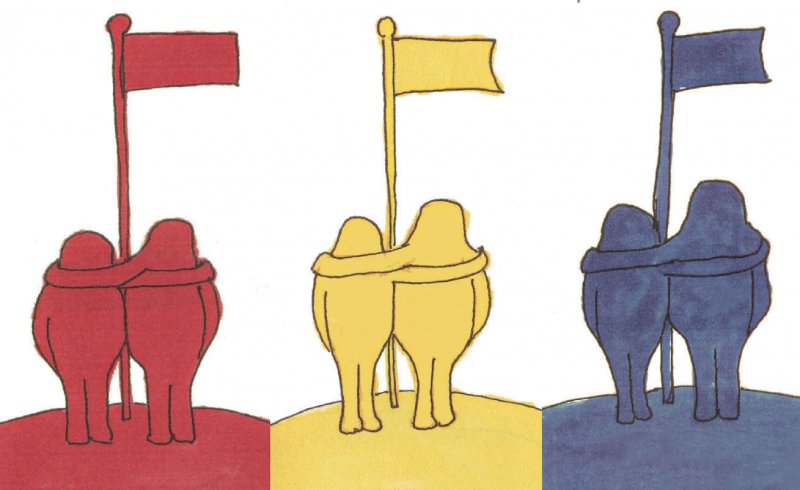

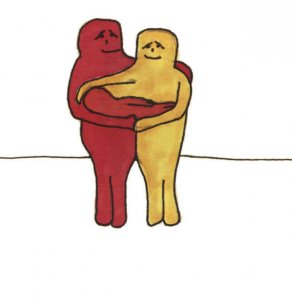

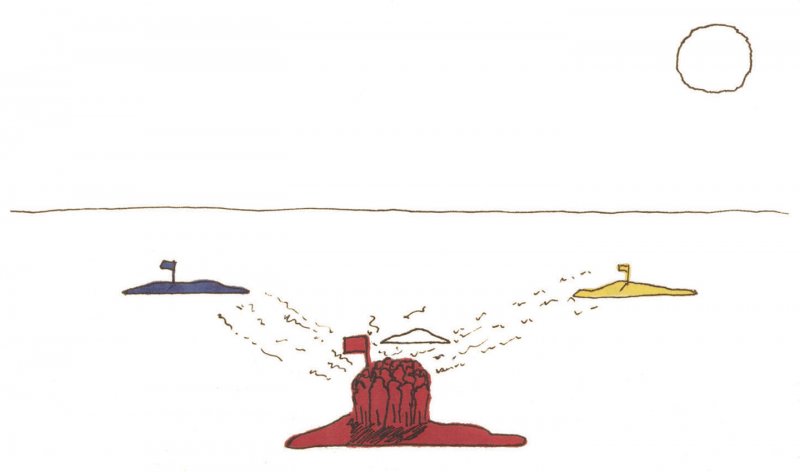

It was in that spirit that her father, Jim LaRue, set about publishing a book Molly wrote and illustrated as a fine arts student at Ohio Wesleyan in the late 1980s. The book, The Reds. the Yellows. the Blues., tells the story of three warring societies that believe, at first, that they are very different from one another. But by the book’s end, a few members from each group start to think there might be a better, happier, more peaceful way to live. Let’s just say there is beauty in rainbows.

In the book’s introduction, Jim LaRue explains: “Thirty years later, the subject of Molly’s little book is more timely than when she wrote it… we live in the midst of a renewed war of words between governments tied to nuclear threats, and Molly’s simple stick figures seem more important than ever.”

In the book’s introduction, Jim LaRue explains: “Thirty years later, the subject of Molly’s little book is more timely than when she wrote it… we live in the midst of a renewed war of words between governments tied to nuclear threats, and Molly’s simple stick figures seem more important than ever.”

Had she lived, Molly would be 54 now. Her father is convinced she would have forged a career helping others — and for good reason. Before Molly and her boyfriend, Geoff Hood, set out on the trail, they had spent several years leading backcountry camping trips for troubled children, teaching them about resiliency, leadership, and friendship. After they finished the trail, they planned to head to graduate school to study experiential education, with the goal of building on the work they had done helping students find peace and strength through nature.

“She loved every minute of being outdoors,” her father says.

“She loved every minute of being outdoors,” her father says.

Hiking the trail was a dream of Molly’s. She’d been backpacking and mountain climbing since the age of 12, heading out into the wild with a church group. After graduating from OWU, she called her family to tell them about the job she’d just taken — her dad remembers hearing the excitement in her voice.

“She says, ‘Guess what! I’m going to be working on this wagon train as a teacher and all of the kids on this train are (gang members) who are being given this one last chance at being free, and I’m going to be helping them!’” Jim remembers.

She radiated a feeling of goodness and joy, and you didn’t feel like there was anything but a pure and honest presence in this young woman. No guile, no affectation, just an open, friendly, warm person who you feel comfortable with. You couldn’t expect anything other than a feeling of niceness and camaraderie or friendship with her.

Emeritus Professor of Fine Arts

Molly spent two years working with the gang members, living out of the back of a truck, then moved to Kansas, where she joined a program for fifth- and sixth-grade students who had family or disciplinary problems. Molly led the kids on three-week backpacking trips, teaching them about cooperation and showing them the peace and beauty the wilderness offered. It was through that program that she met Geoff, who by all accounts appeared to be her soul mate.

“In the course of that year, Geoff and Molly realized that this was what they wanted to do,” Jim recalls. “So they decided to go to graduate school to get the education that would help them build their own program — but first, they decided to hike the trail.”

After the murder trial, Jim and Molly’s mom, Corinne, who died in 2006, decided to try publishing Molly’s book.

“We went to several publishers, but they wanted no part of it because of the circumstance surrounding the kids’ deaths,” he said. “So we gave up on it.”

“We went to several publishers, but they wanted no part of it because of the circumstance surrounding the kids’ deaths,” he said. “So we gave up on it.”

Decades passed, and Jim spent his time restoring homes in the inner city of Cleveland before finally retiring to Medina in northeast Ohio. He bought around 30 acres, built some trails and a little sustainable house that he opens to anyone who needs it, and settled in to his life. In 2006 he went back to Virginia to testify in the re-sentencing hearing of Molly’s killer. The man’s death sentence had been overturned on appeal. Sparing the life of his daughter’s killer was a decision that Jim agreed with, and at the hearing, Jim told him that he forgave him.

Jim didn’t think much about Molly’s book until late 2018, when he sat down to write his annual Christmas letter. He kept coming back to his feelings about the state of the world — too much division, he thought, too much hate — and realized Molly’s book was perfect.

“I told a friend: ‘Molly’s book was written for this day. And I want to publish it,’” he said.

The publishing world is significantly different now than it was 30 years ago — no gatekeeper is necessary to produce a book — and a friend helped Jim selfpublish. He had 200 copies printed. (It is available on Amazon.) The book is exactly as Molly wrote and illustrated it. Jim’s powerfully written forgiveness statement to her killer is included as an afterword.

“It hasn’t reached the New York Times bestseller list yet,” Jim jokes now, “but I’m getting some good feedback on it.”

More important, the book is a way to keep Molly’s spirit of love and peace and light alive a little longer.

“I’m 82,” her father says, “so I was anxious to leave a little memory of her that I thought was useful and important so that when I am gone, she will not be easily forgotten.”

AT continues to draw OWU students