Feature

Intelligence plus character – that is the goal of true education.

A House Reborn

A House Reborn

Construction of new House of Black Culture is underway, with plans to open in January

When Leman Hodges ’74 was a freshman, he suffered unimaginable tragedy when both his parents were killed by gun violence in separate incidents back home in Cleveland. His Ohio Wesleyan classmates raised money to buy him a bus ticket for a trip home. Today, he says his relationship with the students he had only recently met through the House of Black Culture sustained him. “I can honestly say the support I received in this House helped me to stay here and get my education here,” he says.

More than four decades later, MaLia Walker ’19, a triple-major in black world studies, pre-med, and neuroscience from Los Angeles, found a similar bond in the House. “Being at a predominantly white institution, it’s not like a turnoff not seeing your people, but it’s intimidating. You don’t feel as comfortable if you don’t see people who look like you. So I wanted to go where my people were,” she says.

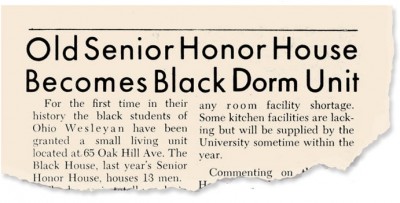

Since it opened originally as “The Black House” in the fall of 1970, hundreds of OWU students have lived in or regularly relaxed at the five-bedroom home, which grew to become a sanctuary of African-American culture, social gatherings, and familiar caretaking. The House was renamed for former sociology Professor Butler A. Jones in 1994. Jones taught at OWU from 1952 to 1969 and headed the Sociology Department for eight of those years. A national leader in his field, Jones submitted 10 briefs to the U.S. Supreme Court in cases involving equal treatment of all citizens.

An article in The Transcript from Oct. 1, 1970, says the former honors house welcomed 13 men its first year. Reginald Surmon ’73, then coordinator of the Student Union on Black Awareness (SUBA), called the House “a start,” and Pete Smith ’71, a SUBA founder and former coordinator, was quoted as saying: “The House seems to be working beautifully as a symbol of black manhood on Wesleyan’s campus. It can only act as an instrument of self-realization of our black students.”

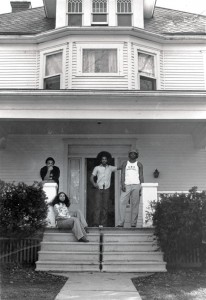

And for decades it has been, for men and women alike. The House was traded back and forth between men and women each year, with room for 10, until going coed in the late 1990s. But after decades of deferred maintenance, the structure at 65 Oak Hill Ave. was a relic of its former self and no longer habitable. The last student residents moved out in May.

Recognizing the symbolic importance of the House, and guided by the impassioned response of alumni, the administration committed to rebuilding it at the same location with many of the same communal features when it reopens in January 2019.

Before it was razed, many of those alumni responsible for the creation and life of the House of Black Culture came back to pay their respects one last time, at an open house and “rite of passage” during Reunion Weekend.

“This place was a home away from home for me, and the students who would come here became my expanded brotherhood,” Hodges recalled in May, his eyes wandering about the family room. “This is the place where we could find our voice on this campus. It gave you a sense of culture. It helped create strong will and a sense of determination. Who knew you could get all that from a house?”

In the late 1960s, OWU’s black students, who made up less than 2 percent of the student body, felt increasingly isolated on campus. At the tail end of the civil rights era, relations between black and white students were still uneasy, untrusting, and uncomfortable. It was still commonplace to hear of civil unrest on campuses elsewhere, and Ohio Wesleyan did not seem immune from potential unrest.

Pete Smith says 1968 “was a very different time. We knew very quickly as black students on this campus that we needed to be change agents. There wasn’t a lot to do on campus socially if you were a black student. We weren’t invited to events around campus. It could be a very isolating place. That was a tough thing to do because everything around you felt like it was already so well established. So how do you fit in?”

Success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome while trying to succeed.

The administration made the Cave available, a small but now venerable meeting spot in the basement of Stuyvesant Hall on campus. But these students demanded more, something that could feel like a real home when their dormitory halls grew too stressful. A spot where they could rest, relax, eat, study, gather, socialize, and do it around friendly, familiar faces.

Smith recalls black students banding together and asking the administration to provide them with a small living unit on campus. “That’s how this all began,” Smith recalls. “This House became a hub, a refuge for the black students on campus. We had to become change agents for Ohio Wesleyan.”

The sentiment is accurate but there was even more to it, recalls Reginald “Reggie” Surmon. “We wanted to add the black experience to this campus and to our education. We wanted to see more black faculty, resources for a black house, and a fund to bring black entertainment to campus,” Surmon says.

What Surmon did not count on was how the House became a survival tent for young people struggling to make the most of an opportunity to earn an education at a highly regarded academic institution.

“A lot of us came to Ohio Wesleyan not classically prepared to do college-level work. So we had to learn study habits, learn the English language in some cases, and we leaned on each other to get it done. This House was the only place on campus where you could feel comfortable facing those challenges together, helping each other. This was an opportunity for us, but we weren’t necessarily prepared for it when we first arrived until you spent time in this House.”

In fact, the retention rate of black students was low during that period because of the struggles many faced adapting to college life at OWU.

“Some black students didn’t make it. They didn’t come back. We’d go on a break, and when you came back to campus a few people weren’t here. It was shocking sometimes because you had no idea,” recalled Bernice Tucker ’74. “For those of us who stayed, this House helped us make it through.”

Aaron Granger ’93, a member of the OWU Board of Trustees, didn’t live in the House as a student, but says he spent enough time there as an undergraduate to know how vitally important it is for campus.

“We want to make this House look on the outside how it has made each and every one of us feel on the inside – a warm, welcoming sense of culture and community that we can all be so proud of,” Granger said at the May event. “The outward physical manifestation of the House publicly announces to those who pass by that the black experience on campus is important. Inwardly, the walls of the House provide a safe environment for building a sense of family and pride that can be explored and ultimately shared with others throughout the University community.

“This moment is too important to sit by and do nothing,” Granger said.

President Rock Jones has been vocal about the University’s commitment to the House of Black Culture and what it stands for, hosting forums on campus with students and participating in an online chat that was live-streamed during the planning phase in April 2017. “Ensuring each student finds their place is a hallmark of the Ohio Wesleyan experience,” Jones says. “We are thrilled that donor support is allowing us to rebuild this critical piece of OWU’s history and future in the same location where it has meant so much to so many.”

Genaye Ervin ’19, a triple-major in business administration, communication, and health and human kinetics sports management from Cleveland, lived in the House her sophomore and junior years and served as moderator. She was a member of the advisory committee (chaired by Granger) that gave feedback during the design and planning phase for the new house. “It’s not like we’re just students and we’re on the committee and we’re just here for show. They’re actually listening to us, so I really appreciate that,” she says.

“I’m really proud to be a part of something of that nature and to be able to say that I did what I could to get funding for the House, and to make sure that the House stayed on campus and that minorities can have a safe place to go to – an actual home instead of just meeting once a week,” Ervin says.

Daniel Delatte ’19, a double major in environmental studies and international studies, with a minor in Spanish, from New Orleans, has never lived anywhere else on campus. “It’s just really weird sometimes being on campus with nowhere to really go and be yourself sometimes; this provides a safe space for it,” he says. “These were the first friends that I made here, people that graduated, they showed me that this school was pretty cool.”

This welcoming sense of home has been passed down through the years, even as the House itself deteriorated. “You could feel the presence of this House every time you would walk in,” says Kenny Williams ’09. “There was always a sense of home, even if you didn’t live here. Even if you lived in a dorm you could come here to get a sense of culture from the pictures and artifacts that have been left behind from people who were here before.”

Kadijah Adams ’04 says 65 Oak Hill was a place for extending learning. “We would host programs that were not only about educating other black students, but a lot of times it was about educating the entire campus,” she says. “It was great to see black students learn in real time about black culture but then also share that information with the larger campus by inviting everyone into the House.”

Rev. Myron McCoy ’77 D. Min., a member of the Board of Trustees, recalled students of different races coming to visit the House and spend time with friends. Using the House as a tool to help bridge racial and other divides through lessons of inclusion must also be part of the House’s future, he said. “By the time I arrived on campus the House was already established and there was a sense of black students becoming one. By the time we left, we left with not only a feeling of being prepared for our careers but with a sense of community and the importance of giving back once you are gone,” McCoy said.

“That’s the foundation of this place, and we must figure out how to make sure that is part of what makes this House important for future students who will come to this campus,” McCoy said. “How do you share that culture from this House with everyone so that they take that with them back to their communities when they start their careers? That’s what will make Ohio Wesleyan feel like an even better place.”

When it opens in January in the same location at 65 Oak Hill Ave., the new House of Black Culture will keep many of the communal attributes that made the former house such a popular gathering space for almost five decades, with many modern updates. The 3,610-square-foot single-story house will have space for 12 students in six bedrooms.