Teaching Moments

Assumptions, Inequalities & Congressional Committees

A 3-minute class with Franchesca Nestor, Associate Professor in the Department of Politics & Government

I'm going to tell you a story about how something that seems really small and narrow—congressional committees—is actually about something much bigger— representation.

The first thing you need to know is that Congress has committees, which split up the work of Congress. Most members of Congress are on about two committees each. So, for example, Congresswoman Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez is on the Committee for Oversight and Accountability and the Committee on Natural Resources.

The way this process works is that as a member of Congress, you're allowed to request what committees you'd like to be on. Then party leaders decide where you'll go, and they may or may not give you the committees that you ask for.

One of the things that political scientists want to know is which committees do members of Congress see as most prestigious? One way they do that is to look at patterns for members of Congress switching committees. For example, if over the course of their careers, a lot of members of Congress switch from the Agriculture Committee to the Ways and Means Committee, that means they prefer the Ways and Means Committee to the Agriculture Committee—it's more prestigious. If, over the course of time, a lot of members of Congress switch from the Armed Services Committee to the Appropriations Committee, that means they prefer the Appropriations Committee—it's more prestigious.

Political scientists keep track of this for all the committees, and they come up with a prestige ranking. Today, the top four most prestigious committees in the House are Ways and Means, Energy and Commerce, Appropriations, and Rules.

There's a problem with this process, though. It assumes that what most members of Congress would do and what they want is what all members of Congress would do and want. It assumes a default member of Congress. That's a problem if you're outside of the default.

We have reason to worry about this. Congress is very white, and over history, Congress was even whiter. So, making these assumptions could lead us to miss patterns of inequality in committee assignments.

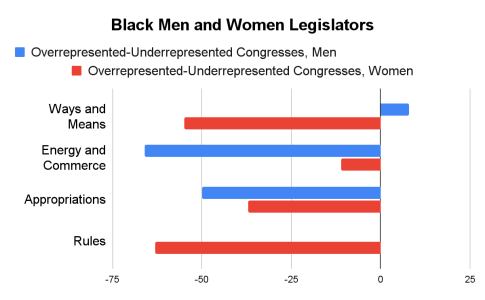

The committee with the highest maximum number of Black legislators in the House has been Small Business, but its overall prestige ranking is 23. And those top four "prestige" committees are not even on the list of the committees with the highest number of Black legislators.

The chart at right shows that while Black male legislators, over time, have been slightly overrepresented on Ways and Means, they have been significantly underrepresented on Energy and Commerce and on Appropriations. For Black female legislators, it's worse. They've been underrepresented on all of the top four committees.

The chart at right shows that while Black male legislators, over time, have been slightly overrepresented on Ways and Means, they have been significantly underrepresented on Energy and Commerce and on Appropriations. For Black female legislators, it's worse. They've been underrepresented on all of the top four committees.

So it does seem that making assumptions about members of Congress has led us to miss certain inequalities in assignment patterns. You know what they say about assumptions: When you assume, you perpetuate legislative inequalities.

We have to do better.