Nashville Q&A

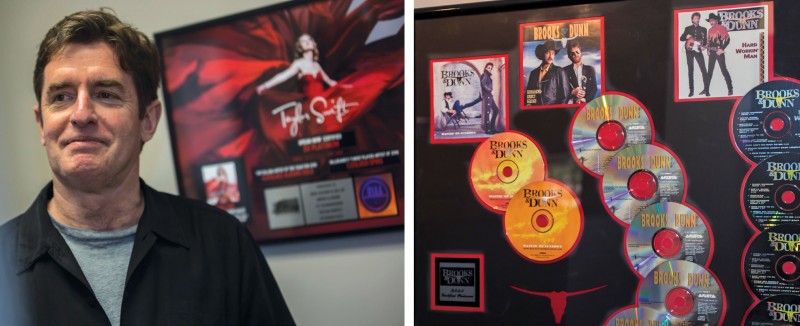

The name Dwight Wiles ’78 doesn’t appear in lights in Nashville; he prefers to leave the center stage to his illustrious clients. As president of Wiles + Taylor & Co., an accounting firm that employs more than 35 associates, Wiles is one of the top entertainment business managers in the industry.

He sits on the boards of the Country Music Association and the Academy of Country Music’s “Lifting Lives” program. His client roster has included Kenny Rogers, Brooks & Dunn, Big & Rich, Cheap Trick, Pretty Lights, Cage the Elephant, and many other acts that he prefers not to disclose (but you’ve heard of them).

We invited singer-songwriter Eric Gnezda ’79 to interview his old Sigma Chi brother. They’ve stayed in touch since college, with Wiles lending his insider guidance and consultation to Gnezda’s creation, the American Public Television series Songs at the Center, which airs on more than 150 stations nationwide and features small groups of singer-songwriters performing “in the round.” Guests have included Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame inductee John Oates and three-time Grammy winner Delbert McClinton.

Gnezda and Wiles sat down together in Nashville to talk about everything from how Bonnie Raitt set Wiles on his music business path when she played Gray Chapel in 1976 to why it’s best to avoid “germing” a famous person.

(The interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

ERIC: How would you explain what you do?

DWIGHT: The joke is: We do everything that nobody else wants to do. There’s a team (manager, agent, record company, publicist) around an artist. We all have our roles, and we all have to communicate and get along and make things happen for the artist. Here we consult and direct the financial side of an artist’s life. We handle everything from tour budgets to taxes to refinancing houses. I always joke, “Our job is to say, ‘No, you can’t afford it.’ ” Nine times out of 10, we get overruled. But that’s our job.

ERIC: Because you do all the things that nobody else wants to do, I suppose they either love you or hate you, right?

DWIGHT: Pretty much, yeah. We’re the good guy sometimes, if we can help them get a loan. We’re the bad guy if we say, “That’s not a good idea. You shouldn’t be doing that.” Really, I look at our job as providing their team with information. An artist might say, “I want to take another person or two on the road with me.” We show them what it will cost for payroll, payroll taxes, workers comp, and per diem for this “investment.” Most people make investment decisions based on hopefully getting a return on their investment, correct? Sometimes that’s lacking in our artists.

ERIC: But artists are also big risk takers, aren’t they?

DWIGHT: They are risk takers, yes, although the artist’s personality is such that most of them are not what we would call “savers.” They are spenders. I can’t tell you the reason for that. Sometimes it’s because most of them grew up having nothing. Once they have some success, they want to prove it to the world by purchasing material things.

ERIC: But artists are also going to look at what they think the best decisions are artistically, right? That’s the balance.

DWIGHT: That’s the balance, and I’m not against that. I started with Brooks & Dunn in 1992. Every year, they would spend lots of money on their stage set. They were smart enough to understand that if radio ever stopped playing Brooks & Dunn, they could still make a career from their live performances because they’d be known for giving people a great show. Now in their particular case, it worked out. It doesn’t always work out.

ERIC: The secret to success in Nashville is learning how to just hang out. Then, when the opportunity comes, being able to deliver the goods. You’re the ultimate hanger-outer. Would you be willing to share the story of how your ability to hang out resulted in one of today’s biggest stars signing with you?

DWIGHT: Sure, but I can’t mention his name. There’s a little grocery store around the corner from my office called the Turnip Truck. It’s a natural-foods store. I go there virtually every day, any day that I don’t have some kind of business lunch. Five, six years ago, there was a guy working there as a cashier. Honestly, he was miserable, just a miserable cashier. You could just tell he wanted to be anywhere else in the world but the Turnip Truck. Never knew his name. I’d just chat him up a little bit when I was going through the line. I’d try to make him smile once in a while and probably never succeeded, but I’d try.

Anyway, he disappeared at some point and then an artist manager-friend of mine, whom I’ve done business with for many years, called and said, “Hey, I want you to meet this new artist of mine.” They came in and the artist turned out to be the former cashier from the Turnip Truck. And the new artist paid me the biggest compliment of my music career. He told his manager that I treated him with the same respect as a cashier as I did as a potential client.

That’s what I want. It didn’t matter that this person was a musician or not. I tell my employees to do the right thing. Be nice to people. You don’t have to talk business with them at all. Just get to know them, and do what you say you’re going to do. It’ll pay off in the long run. (Editor’s Note: This artist has released three albums and recently won a Grammy.)

ERIC: So it’s a cliché, but the stars are just people…

DWIGHT: OK, so I’ll tell you another story. I was at a TV taping back during the Nashville Network days. Pam Tillis was — and still is — my client. Her dad, Mel, along with Bobby Bare, Jerry Reed, and Waylon Jennings, had a super group called Old Dogs.

I was backstage and — this was not too far from the end for Waylon — I mean, he was not in good health. He had a cane and he wasn’t moving very well. He was by himself, just sort of leaning against the wall. My stepdaughter knew Waylon’s son, Shooter. I thought, ‘Well, you know what, I’m going to go up and say hi to Waylon and introduce myself.’ I’ve been around enough famous people that I feel like I kind of know my boundaries. In the industry we call it “germing,” by the way, which is going up to a star and just making a babbling fool of yourself.

Anyway, I went up to Waylon, and I can see the look in his eyes as I’m walking up to him. He was looking at me like, “I don’t want to freaking talk to you, you idiot.” But I said, “Hey, Waylon, Dwight Wiles. I know Shooter.”

As soon as I said “Shooter,” his face just lit up. He said, “Really, how do you know Shooter?” And we had this conversation for five minutes about Shooter and my stepdaughter, and we were just two dads talking to each other. Then I just very respectfully said, “It was great meeting you, and I’ll see you later.” I could still remember that look he gave me, though, when I came up to him — “Don’t you dare try to talk to me.”

ERIC: You’ve always had a gift for putting people at ease, connecting with different types of people.

DWIGHT: Thanks. I feel that the liberal arts education that I got at Ohio Wesleyan really prepared me for this job. I didn’t get the accounting education there. That and the CPA designation came later. OWU taught me to deal with a variety of situations, personality types, and to learn from our differences and, most importantly, to communicate.

The class that prepared me the most for my business life was Report Writing, taught by Libby Reed, who I’m sure many OWU students remember. It’s hard to forget her and her red-ink edit pen.

ERIC: And it was an out-of-the-classroom experience at OWU, in fact, that literally gave you your start, wasn’t it?

DWIGHT: Yes, my sophomore year. The Bonnie Raitt, Little Feat concert. Doug Kridler ’77 (now president and CEO of the Columbus Foundation) was chairperson of the Major Attractions Committee (MAC), and he booked the concert at Gray Chapel. That was the first show I ever worked. I got to see all the behind-the-scenes activities, all these people running around backstage working, like the road manager and the road crew. And the light bulb went off, and it was like, “Whoa, people do this for a living!”

DWIGHT: Yes, my sophomore year. The Bonnie Raitt, Little Feat concert. Doug Kridler ’77 (now president and CEO of the Columbus Foundation) was chairperson of the Major Attractions Committee (MAC), and he booked the concert at Gray Chapel. That was the first show I ever worked. I got to see all the behind-the-scenes activities, all these people running around backstage working, like the road manager and the road crew. And the light bulb went off, and it was like, “Whoa, people do this for a living!”

When I was chairman of the MAC my senior year, I booked and became friends with the Columbus-based band McGuffey Lane, later signed by Atco/Atlantic Records, and their manager, Cliff Audretch. He gave me my first real job in the music industry basically as their road manager. Cliff and I remain friends and continue to work together to this day.

ERIC: I still say Bonnie Raitt at OWU was the best concert I’ve ever attended. Freebo (Daniel Friedberg) was playing bass and Billy Payne was on piano. I love to tell the story of how Bonnie did two encores and told us that if we kept showing this kind of appreciation for artists, we’d get “the cream of the crop.” Then, to make it even more extraordinary, Bonnie and Little Feat were not touring together, so it was a one-off combination Doug was able to put together just for OWU.

DWIGHT: And Lowell George was fronting Little Feat. We saw something really special — Lowell George performing. He died about three years later. But my entire life, since that night when I was a sophomore, has been about the music business. And Doug has certainly been one of my mentors and a friend. We still get together and are in touch frequently.

ERIC: To take the story full circle — 25 years later — the final concert Doug booked when he was president of the Columbus Association for the Performing Arts was Bonnie Raitt. You also worked together to produce the first concert in the Branch Rickey Arena — Chick Corea and his band, Return to Forever, featuring Stanley Clarke. And you worked the Hall and Oates concert, too, didn’t you?

DWIGHT: Yeah, and then just a few years ago, I saw John Oates at an industry function. He was sitting at the table next to me at a dinner for the Nashville Songwriters Association International, and I noticed one of my clients talking to him. I thought “Oh, what the heck, let me go say hi to him.”

I went over and introduced myself and said, “Hey, you’re kind of indirectly responsible for me being in the music business.” He said, “Oh yeah, how’s that?” I said, “Well, one of the first shows I ever worked as a stagehand was in college at Ohio Wesleyan University.” He said, “I remember that.” He didn’t remember me, of course, but did say, “I remember playing Ohio Wesleyan.” I’m thinking, “No you don’t.” But maybe he did. Maybe he has a great memory, but those moments are what make this industry so much fun.

ERIC: Interacting with celebrities is part of your daily business. But you’ve always preferred to be in the background, which takes a special kind of personality, one that is the opposite of what is found in most of the music business. Have you always been that way or is it something you learned?

DWIGHT: I’ve never really been comfortable with being in the spotlight. It’s just not my thing. I don’t know where that comes from. That’s true in a lot of facets of my life. For example I am not active with social media. I’m always a little leery when I’m in a photo with an artist, which I am once in a while. I think the business manager needs to be out of sight. We’re more valuable to our artist/clients in the background than we are trying to make the headlines.

ERIC: At the beginning of your career when these things were happening and you were going to the Grammys and the CMA Awards and all of those high-profile events, was there an excitement about that?

ERIC: At the beginning of your career when these things were happening and you were going to the Grammys and the CMA Awards and all of those high-profile events, was there an excitement about that?

DWIGHT: Of course there was, although I was — and will always be — obsessed with the music more than anything else.

I grew up listening to WMMS in Cleveland, which, of course, was one of the most influential rock stations in the country. They broke Bruce Springsteen and a lot of other people. My freshman year, there were four or five of us who drove to John Carroll University to see Bruce Springsteen and the original E Street Band, including David Sancious on keyboards and Clarence Clemons on sax. And a friend of mine from Nashville whose son goes to John Carroll University told me recently that Tim Russert (the late NBC moderator) was the concert chairman at John Carroll. So Tim Russert was the one who brought Springsteen to Ohio.

Looking back, the night made even a deeper impression upon me. I played some guitar growing up, and still do — very poorly — and I realized early on that I wasn’t going to make my living as a guitar player. But, as I mentioned, once I discovered there was a music business, I wanted to make my living in it. Good fortune, lots of hard work, and my passion for the business of music still make my job exciting and fun every day.

Article by Eric Gnezda ’79 photos by Chad Driver