Methods

During the 2021 school year, participants were recruited from Ohio Wesleyan Early Childhood Center. Participants, teachers, and parents were made aware of the study. Parents received a consent form with a description of the study to provide consent for their child. All children who participated also provided assent to participate. There were 72 total subjects ages 3-6 (females n=34, males n=38, mean age =59 months).

This study employed a quasi-experimental crossover design whereby the researchers divided the participants into two groups that undergo an experimental week (yoga treatment) and a control week (no yoga treatment). One group of participants were randomly selected to first experience the treatment week, while the other group would experience the control week and then the groups would switch. These two groups were made up of the 6 "classrooms" already present at the ECC (3 classrooms per group).

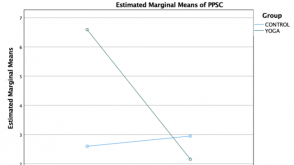

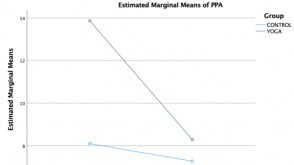

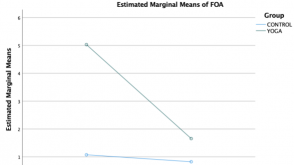

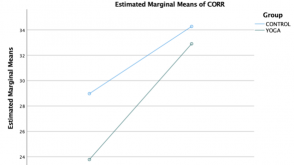

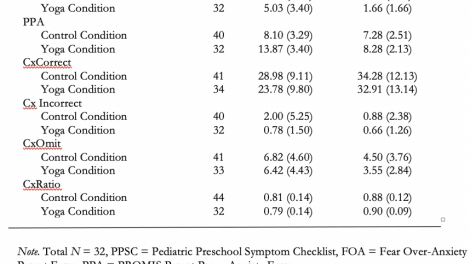

The relevant measures included the preschool pediatric symptom checklist (PPSC) which is designed for children between 0-65 months. It is intended to be filled out by the parent of the child, the Parent Proxy Anxiety-Short form 8a where was an eight-question survey that is filled out by the parent, and the Fear Over Anxious (Ages 3-7) Parent Report Fixed Form which focuses on the parent's report of children's anxiety. All three forms were changed into teacher versions as well. The children also did a cancellation task, an age-appropriate, timed task where children mark off as many animals (horses and birds) in 90 seconds to determine the child's attention and concentration.

The yoga intervention consisted of a 15 minute standardized video, entitled "Yoga for Kids with Alissa Kepas" (above.) All children viewed the same video. Alissa Kepas introduces the poses by using animal and nature poses. She adds in interactive sounds to engage the children. Her poses include cat, cow, downward dog, sun salutation, upward dog, warrior, gorilla, tree, butterfly, etc.

Both groups conducted a baseline test of relevant measures one week before the intervention began. For the experimental intervention week, the group was exposed to the yoga treatment on two occasions, one time as a practice session, where no measures were collected. Again, a second time, where the relevant measures were recorded post-yoga. The control group was not exposed to yoga and the relevant measures were recorded at the end of the week. The control and experimental group were exactly the same in every regard, except the control group will not receive the yoga intervention.